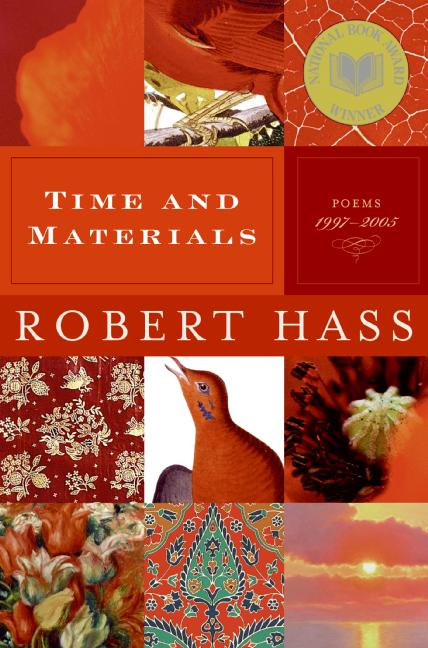

Time and Materials: Poems 1997-2005 by Robert Hass

Time and Materials: Poems 1997-2005 by Robert Hass

Ecco Press, 2007

'Poets are turtles', the American poet William Matthews once remarked, meaning that with few exceptions, the good ones mature slowly, often producing strong verse into their sixties, an age that he, unfortunately, didn't reach. Matthews shared with Robert Hass a rare skill for the long, intricately made, rhythmic lyric, which Hass has been perfecting for over thirty years. He has translated Milosz and Tranströmer, and served as U.S Poet Laureate during the Clinton years, a role which involved foregoing his own writing in order to raise awareness of the importance of literacy and the environment.

Language and landscape have always dovetailed with a rare effortlessness in Hass's best work. Each of the Californian-born poet's collections has explored, among other things, the West Coast flora and fauna, human relationships, and the limits and possibilities of nomenclature and description. His fifth and latest collection, Time and Materials: Poems 1997-2005, inhabits familiar territory with typical inquisitiveness and a growing distaste for political and environmental violence.

As a friend recently pointed out to me, Hass is writing for a lot of people. And I agree.

Yet his trick is to make you feel you are the only person in the audience. Time and Materials is simultaneously personal and political, sensual and straightforward. In the past, Hass has favoured a lightness of touch, and here also, he is wary of rhetoric, paraphrasing Basho in 'Winged and Acid Dark':

Basho told Rensetsu to avoid sensational materials.

If the horror of the world were the truth of the world,

he said, there would be no one to say it

and no one to say it to.

I think he recommended describing the slightly frenzied

swarming of insects near a waterfall.

Characteristically enamoured with the natural world, here is the poet wrestling with how to address big issues without stymieing his aesthetic disposition. It is a question this book resolves in poems like 'A Poem', which examines the casualties of the Vietnam and Iraq wars. His holistic, impassive analysis is startling and to the point – morality through statistics – a technique he repeats in a handful of poems. 'The human imagination does not do very well with large numbers', he reminds us in another poem. In 'Bush's War', he is more elusive at first; beginning with an evocation of the German countryside that soon collides with a jolting meditation on twentieth century war-torn Europe. The syntax is acrobatic, rendering innocence and brutality as two sides of the one coin spinning in slow motion through history.

Elsewhere he is more light-hearted, imagining Nietzche eating sausage his mother mails him, or Whitman in the library, 'researching alternative Americas'. Eavesdropping on the secret lives of writers is a signature manoeuvre into history for Hass. In 'Rusia en 1931', from his previous collection, Human Wishes, he imagines the chance meeting of the poets César Vallejo and Osip Mandelstam in Leningrad. Here, place, political history and personality intersect in the imagination. It is an arresting tactic that has mixed results.

In 'The Return of Robinson Jeffers', a much earlier poem from Field Guide, Jeffers is resurrected to stroll the Californian coast and rue his former earthly preoccupation with stone and human anguish. Hass sponsors 'a plain man's elegiac tenderness' in Jeffers' ghost. It is a poem that Hass's contemporary Louise Gluck thinks is 'either very touching or extremely arrogant'. I suspect it is both.

Elsewhere in Hass's oeuvre, one might glimpse Marx in the library, or Randall Jarrell in tennis whites. There are nods to Checkov and the Japanese masters. This belletristic obsession might seem vacuous were it not coupled with broader historical phenomena. In Time and Materials we're treated to cameo appearances by Milosz, Ashbery, and the niece of Emily Dickinson to name a few. Hass is one minute thinking of Ezra Pound, the next he's implicating the political elite in a prostitute's proposition on a Bangkok street:

Here is more or less how it works:

The World Bank arranges the credit and the dam

Floods three hundred villages, and the villagers find their way

To the city where their daughters melt into the teeming streets,

If this is oversimplification, he somehow gets away with it. It's the 'more or less' that imparts a relaxed, almost off-the-cuff tone in his reprimand. Another poet might dare to implicate Halliburton in Thai prostitution, but few could achieve the resonance and sense of interconnectedness Hass does.

There is also the playful 'Poem With a Cucumber in it', or shorter lyric pieces born from a love of oriental forms; and his translation of a Tranströmer poem, 'Song', which mimics the music and imagery of the Finnish epic The Kalevala, with less success – struggling, despite intense tonsil-flexing and shimmering, luminous language, to convey much to readers unfamiliar with the poet-singer/protagonist, Väinämöinen (whose name is surprisingly misspelled). The problem is contextual and tonal, though it does little to hinder the cohesiveness of the collection. In the notes, Hass comments that he included his translation for the contrast it provides to the ways of thinking about the natural world in one of the book's strongest poems, 'State of the Planet'- an eight page masterstroke that is both elegy and plea, because, as he puts it, 'the earth needs a dream of restoration'.

This big language finds a counterpoint in more acute observations of a child walking in rain, 'Inside the backpack, dog-eared, full of illustrations,/ A book with a title like 'Getting to Know Your Planet'. Here he is speaking to himself, to humanity, and to the ghost of the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius. It might not say anything we don't already know about the state of the planet, but the way it says it is unlikely to be equalled anytime soon. It is a kind of essayistic lyricism which enables didactics to rest alongside aesthetics.

Inherent in Hass's poetics is the Rilkean sense of the eternal amateur concerned with the limits of language. Take for instance the poems 'The Problem of Describing Color' and 'The Problem of Describing Trees'. Indeed, for a poet as skilled as Hass, this may seem like an act of self effacement, and it is. He surrenders to the limits of naming and is humbled. Yet the possibilities are ever seductive, and descriptive extrapolation is never far away. Seemingly at home in the sensual, he is suddenly distracted by the oddities of everyday speech. The poem 'Etymology' begins:

Her body by the fire

Mimicked the light-conferring midnights

Of philosophy.

Suppose they are dead now.

Isn't 'dead now' an odd expression?

Suppose 'who' is dead? Her? The 'light-conferring midnights of philosophy'? This is puzzling stuff, and some readers will surely shake their heads. Randall Jarrell once wrote that one sort of clearness shows a complete contempt for the reader, just as one sort of obscurity shows a complete respect. Hass will never give you the whole story. To read him is to use your imagination – a prerequisite to understanding any poetry as 'accessible'.

In the introduction to Hass's debut collection, Field Guide, Stanley Kunitz writes: 'The country from which he has his passport is the natural universe, to which he pledges his imagination'. 'Natural universe and moral universe coincide for him, centred in a nexus of personal affections'. You get a sense that, in 2007, Hass is still coming from the same 'country'. At home in a Sierra meadow, he'll take the waterfall over the war, but can not bring himself to shy away from either. Time and Materials is a generous book that contains many pleasures, and just as many questions.