“Domain is without exception the most difficult and challenging poetry collection I have ever tackled. It involved almost four years of steady research and writing. It had a profound effect on me, and caused many a night of uneasy sleep. I found myself quite overcome by a lot of the imagery and literature, which hung around me in a sad, invisible, cloying sort of way.” Ian McBryde talks about his latest collection of poetry.

“Domain is without exception the most difficult and challenging poetry collection I have ever tackled. It involved almost four years of steady research and writing. It had a profound effect on me, and caused many a night of uneasy sleep. I found myself quite overcome by a lot of the imagery and literature, which hung around me in a sad, invisible, cloying sort of way.” Ian McBryde talks about his latest collection of poetry.

In an author's note to your new book of poems, Domain, you state that this collection “represents a serious attempt to understand an evil beyond comprehension. Having finally completed my collection, I understand such bleak history even less than I did at this book's conception.” Could you talk us through that a little more? Was that paradox or contradiction (understanding vs incomprehension) present for you at the book's outset?

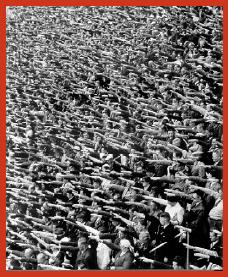

IM: I suppose the initial impetus was an interest in that particular period of History, fostered in my youth. This is actually the first and only time that I've had an author's note at the start of a collection, and it was meant to explain why I had tackled this subject matter. I was grimly fascinated as to how such a monumental evil could not only thrive, but be so well organised and enacted over such a lengthy period. The collection really began years ago, when I wrote a poem on Eichmann, having watched a programme on his trial on SBS. Then about six years ago I wrote poems on all the main Nazi figures; Heydrich, Goebbels, Himmler, etc., again prompted by SBS specials on the Third Reich. I then found myself immersed to the degree that a whole book seemed like the most pragmatic way to go in dealing with the surfeit of information I had absorbed. And yes, the paradox at the end was the same as at the beginning, and continues to exist for me. I still don't understand how the whole terrible uncoiling of events not only happened, but was allowed to happen, and accelerate.

What does the word “domain” mean to you? Is this domain similar to other domains you have explored in your writing? Is it a counterpoint to the idea of Zones in the immediate postwar aftermath?

IM: The title Domain is meant only to indicate the absolute sway that the Third Reich held over Europe. It is not intended as a post-war reference to the NATO dispensation of land after 1945. I have explored vaguely similar themes in other earlier poems, such as the Manson Family saga.

Is the “domain” a masculine one? What's your take on the masculinity of Nazi horror?

IM: It was an almost entirely masculine effort, as so much of the world's darker history is and probably always will be. There was a notable absence of any female high-ranking Nazi leading players. The women whose names are associated with the Third Reich were generally regarded as “muses”, such as Winifred Wagner, or lovers such as Eva Braun. One notable exception would be the actress and film-maker Leni Riefensthal, who quite avidly encaptured the more visual and less insidious aspects of Nazi Germany through films such as “Triumph of the Will” and other propoganda-based cinematic works.

What impact did film have on your response to the Nazi holocaust? Was it easier to respond to film than, say, to photographs, or written descriptions, recollections? Why would that be?

IM: Film had a galvanic impact on the poetry. I read a great many books on the topic, but there is something so undeniable about any raw, actual footage; it exists, it is there in naked colour or (even more powerful somehow) black and white before one's eyes, and cannot be enhanced or over-shadowed in any way by the personal slant of any specific writer or historian. While I learned a great deal from the bibliography and websites listed at the back of Domain, it was really through films of the camps and surviving holocaust and Third Reich footage that one gets the grim, true, undeniable reality.

There has been much discussion about Adorno and the interpretation of his maxim about poetry and auschwitz (I'm paraphrasing but “that after Auschwitz there can be no lyric poetry” – “Ob nach Auschwitz noch sich leben lasse”) including claims that his original quote has been distorted by Nazi apologists – what is your view? What do you think Adorno meant? Did Adorno's philosophies inform your work?

IM: No. I'm not familiar with Adorno's philosophies, and in actuality I deliberately restricted myself to purely historical literature, with the exception of writers like Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel, whose personal recollections are invaluable to anyone studying the holocaust and its place in history. I think the quote you mention possibly meant that after such travesty inflicted on humanity, what would be the point of poetry, any poetry? How does any artist, no matter what their milieu, create anything even approaching tenderness or benevolence or innocence in the face and aftermath of such horror?

Have you been to Germany? Was / is a sense of place necessary in order to write these poems?

IM: I was in Germany very briefly, several years ago, but not for long enough to really absorb the place, let alone explore any of the places made famous by the war. I have several friends who have visited the sites of Dachau and Auschwitz, to whom I have spoken at length about their impressions.

A German-speaking writer such as Gunter Grass in The Tin Drum and Crabwalk writes about the ways in which “everyday” German citizens allowed the Holocaust to happen – what's your view?

IM: A very poignant question. The Tin Drum is a good example. Most people today find it difficult to believe that the average German civilian alive during the 1930s and 40s knew nothing about what was really going on. I personally find it untenable that those who lived near the camps were completely ignorant of the activities enacted therein, what with the cattle trucks coming in full and leaving empty, the singed smell of the constant smoke and flames from the ovens, etc. There is some amazing footage of Allied soldiers forcing the inhabitants of towns near the death camps to walk through the camps after liberation, and view the results of the horror at first hand. But I also think it should be remembered that the level of fear and intimidation present during this time would have forced not only the German populace, but any populace, to turn their heads away and pretend either that it wasn't happening, or that it was safer not to acknowledge it in any way. Even Albert Speer, in his quite fascinating autobiography that he smuggled out of prison, has varying degrees of self-exoneration. He acknowledges that he knew slave labour was used in his armaments factories, but he denies knowledge of the concentration camps, and of their purpose. I don't know that we will ever be able to ascertain to what degree the general populace knew what was happening.

How does writing poetry about such subject matter as Dachau colour your perception of everyday life today? How did you feel after reading or writing these poems?

IM: Domain is without exception the most difficult and challenging poetry collection I have ever tackled. It involved almost four years of steady research and writing. It had a profound effect on me, and caused many a night of uneasy sleep. I found myself quite overcome by a lot of the imagery and literature, which hung around me in a sad, invisible, cloying sort of way. My long-suffering partner would I'm sure say, quite correctly, that she found me difficult to be with much of the time during the writing of Domain. I've now taped over all the holocaust and WW2 footage recordings I made from television documentaries. I'm very relieved that this book is finished and away from me, and out in the world.

What was your experience of reading Mein Kampf?

I found it rambling. I ended up skimming through it rather than perusing it from cover to cover, although you can sense the seeds of mesmerism and utter self-conviction that were to serve Hitler so well as an extremely hypnotic orator and public figure.

Were any of the websites you visited neo-nazi – how did it feel to read them?

IM:I hit on a White Power one by mistake, and exited in a hurry.

There's a grim humour to poems like “a long way to tipperary” while other poems, in terms of form, employ some unusual forms – tanka, haiku, visual poetry – why did you choose these forms?

IM: I'm traditionally a free-verse poet I suppose, although I've always been intrigued by form, and it made sense to attempt to utilise form apropos of this particular collection. I found the villanelles quite exacting and challenging, and while I've written some haiku before, certain poems in Domain seemed to call for haiku and tanka. As for the concrete poems, that's my first attempt at this form, but again, the tone of the collection made certain imagery immensely useable.

You dedicate the poem “Flashless Cordite” to another McBryde – can you tell us a bit more about this person?

IM: Dr W.A.E. McBryde is my father, who, before his retirement, was a distinguished inorganic chemist and professor. They still give out a national medal (named after him) each year in Canada to the most promising upcoming chemistry student. In the late 1930s he did secret research work first in Toronto and then in Virginia, working on the theory of “flashless cordite” whereby the flash from naval gun muzzles could not be seen at night by enemy ships. I've sent him a copy of Domain, and he is quite tickled to see the poem dedicated to him.

In this issue we've published some of your Slivers – tell us a bit more abouty these.

IM: This is an ongoing project that I've been working on over the last year or so, and consists entirely of one-line poems. It's an attempt to tell a whole poem in one line only. The poems are mainly intended to stand alone, as separate pieces, but could also be read as part of a whole. I love the notion of such brevity.

What's next?

IM: Well, besides my Slivers, I have another manuscript basically completed, entitled “The Adoption Order”, which is a gathering together of all the poems I have written and am still writing about having been adopted. I have also started a new sequence of poems, which might become a book, about Marilyn Monroe, whom I find a most intriguing person, with many unanswered questions about her life and death. It's a fascinating story. And, together with Melbourne musician Greg Riddell, we (as The Still Company) are releasing a new CD soon of my poetry set to musical and/or ambient backgrounds. So I've got lots of work ahead of me, which is great.

Read Ali Aizadeh's review of Domain.