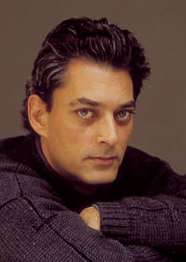

Paul Auster's career has meandered from poetry to prose to filmmaking, and gives no indication of slowing down just yet. The Brooklyner spoke to George Dunford about collaboration, word-houses, chasing the perfect page, and his twelfth novel Man in the Dark, set to hit shelves this September.

Paul Auster's career has meandered from poetry to prose to filmmaking, and gives no indication of slowing down just yet. The Brooklyner spoke to George Dunford about collaboration, word-houses, chasing the perfect page, and his twelfth novel Man in the Dark, set to hit shelves this September.

Your next book Man In The Dark has been talked about as a 'political novel'. What can we expect from that?

It is a political novel in some senses and then in another sense it's a family novel and it's also a novel about memory. It's many things all at once. The essential thing to know is that it's an aging man in his early 70s, his wife has died within the past year. He's been in a bad car accident and ruined one of his legs and is pretty much incapacitated, and he's living in the country with his daughter and granddaughter. The daughter is in her forties and the granddaughter in her twenties. It's just the three of them in the country – each one suffering for different reasons. And the whole book takes place in one night as he's lying in bed unable to sleep. He makes up stories to pass the time and to ward off memories he doesn't want to revisit. The larger story that he tells himself during the course of the night is a rather fantastical tale of a civil war in the United States. So yes, there is politics, and the Iraq war is certainly an element in the book, but it's more than just that.

You once said of your writing process that 'every day you learn how stupid you are.' Is that still true?

Absolutely. It's daunting. You make so many mistakes in the course of writing a novel. So many bad sentences come out of your pen that it's really humiliating. I mean it. I do feel quite stupid most of the time, but you keep pushing then eventually if the project is worth doing, something is gonna happen. You'll get there.

The difference between being young and old is that when I was younger if I got blocks I would panic and think that the entire project is about to fall to pieces and I wouldn't be able to push forward. Now I know that if it's worth doing I'm going to find a way, because it's already there somehow, inside me, and I just have to keep digging deeper and deeper and eventually I'm going to find it and pull it out of myself.

How do you keep digging?

I think you just keep thinking. You keep thinking about how you're telling the story and what you're telling and why you're telling- The mind works – particularly my mind – by association, so it's very easy to go spinning off track and make one or two leaps and suddenly you're taking the wrong road. So what we do then is go back to the sentence where you started to go off track and re-think your itinerary.

In the film Smoke you write about a blocked writer called Paul Benjamin. Do you ever experience block?

I've had moments when it's very difficult to write. I think it's true of every writer – most writers anyway – and you just have to live through it and get through it. It's uncanny- I'm writing a new book now. I started a few months ago and it's going very, very slowly. I barely know what I'm doing. I feel there's something to it. It's not that it's not worth doing, but I don't fully understand it yet. And I'm inching along as if I'm crawling on my hands and knees everyday. I'm all bloody from all the gravel that's been ripping my skin apart. Where as Man In The Dark just came pouring out of me. It was as if the book was already sitting inside me and I was taking dictation. It all depends. Every book comes out differently.

What about the good days when you feel like you're really hitting it?

I get scared because I think 'Oy, maybe tomorrow it's going to be pretty bad' so I try not to get too excited. I think 'Alright, so I put in a good days work. Let's hope I can do it again tomorrow.''

Do you still use an old Olympia typewriter?

[Laughs] I still have the same old typewriter. I like it; I'm attached to it. It's a very good machine and I don't see why I should change.

But you're not a complete Luddite: you have a MySpace page-

I have a MySpace page? Well, I never did it. I don't know who did it. I never look. I know there's a website about me, but I don't have anything to do with it. Someone in England started it about ten years ago. People tell me it's rather thorough.

I actually write everything by hand, either with a pencil or a fountain pen. I do have an assistant who helps me answer correspondence and she helps me with practical things. She comes in once a week and we go through the pile of things that I've received and she uses email to answer people. So in a sense I'm taking advantage of it but I'm not doing it myself.

In your work, the notebook is a real trope whether it's The Red Notebook or a found notebook. What makes you keep returning to notebooks?

I always write in notebooks, so notebooks are almost a synonym for writing itself. A notebook is a house for words, so I'm quite preoccupied by them.

Is it true that you believe in writing one perfect page per day?

Some days I only manage to write half a page, some days I write three pages. I work in the notebook and I start changing sentences, crossing things out and writing in the margins. It becomes so hard to decipher. Once I have a reasonable approach to a paragraph I type it up, then I start attacking the typed page with my pen or pencil, then I type it up again. I probably revise everything about a dozen times, twenty times. It goes through lots and lots of changes as I go through the book.

Everyone says that my style is so clear and lucid and easily digestible, well it's because of all the work [laughs]. You work really hard to make it look easy. But it's not easy, at least not for me.

You started relatively late in life as a novelist. Your book Hand to Mouth details your work before you became a writer including work as a seaman, a translator and a puzzle maker. And you can see how these jobs have informed your work – should writers work outside their fields?

Yeah, well it's true, but that was a long time ago now, since I was in those jobs in my twenties and early thirties, but those are indelible experiences and I'm glad of the different kinds of things I did when I was young and the different people I ran across in my travels. I always found that blue-collar jobs were more interesting than white-collar jobs: you tended to meet more fascinating people and to learn more. The work itself might have been drudgery but the environment you're living in is more stimulating. I learnt a lot from those experiences.

There was a long period where I was trying to make my living as a translator, but it meant that I was sitting on my ass all the time. I was translating to make money and then trying to write my poems and essays also at the same desk, in the same chair all day, and I don't know if that's the best way to live.

You yourself had a car accident that left you temporarily immobile and I'm wondering if Man In The Dark isn't a dark imagining of your own life?

I don't really know. I made this big break when I wrote Travels in the Scriptorium, that short book about an old man in a room. That book started with an image I couldn't get out of my head. It was just there. Day after day. Week after week. It was just haunting me. It was very simple: an old man dressed in pyjamas sitting on the edge of the bed, hands on his knees, leather slippers on his feet and he's looking down at the floor. That's what I kept seeing. And after a while I said I have to start exploring this image. What does it mean? Why am I seeing it all the time? I came to the conclusion -whether I'm right or wrong I don't know – that maybe that was a projection of myself twenty or thirty years in the future. Myself as an old man. The book came out of that. This new book is definitely a response to Travels in the Scriptorium – they go together. Travels takes place in one day and Man In The Dark takes place in one night. And this third thing that I'm writing is part of some sort of triptych of novels, all of them having something to do with war in one form or another.

Do you feel like Man In The Dark, as a response to Travels, is in some way unfinished? Is that why you're writing a third book?

I think there's a kind of inner dialectic that goes on in the mind of a writer. You start something and then you think of the antithesis, a response. That's definitely the way my mind works. One work answers another or contradicts it or subverts it or takes in a completely different direction.

For example, early on back in the 80s I wrote a novel called Moon Palace and one of the last things that happens is that the narrator/hero is driving across the American West in a red car and this car is stolen and he continues the trip to California on foot. Now, after I was finished with the book I said to myself, 'I want to get back in that red car.' So I started my next book The Music of Chance with a man driving around in red car. The two books have nothing to do with each other, but there is that link which is the red car.

You've done a lot of collaboration, from the film Smoke to recording music with Brooklyn band One Ring Zero. And the graphic novel City of Glass with Art Spiegelman – what was that like? Is it difficult surrendering your words?

The only thing I asked of them [Art Spiegelman and other graphic novel collaborators] was that they confined themselves to words in the novel: you can cut out as many as you want but don't add any of your own. And so they stuck to that and that was my main concern. I think the visual material is very compelling.

As far as filmmaking goes, I've been involved in making the films. It's not as though I've handed over my books or my scripts to somebody else and let them do it. It only happened once: it was a film version of The Music of Chance back in the early 90s and there I had nothing to do with it. The director wrote the script and was the editor and it was their film entirely.

How was that?

It went okay. I think the film was not bad, it's not great. It's a decent film. It kind of robbed me of the desire to have my books turned into movies so I've pretty much said no to everybody since. I don't think- My novels are too crazy to be turned into films. I can't think how they could work.

I believe there's talk about a film version of one of my favourite books, In the Country of Last Things?

It's the one project I've endorsed. It's a young Argentinean filmmaker and I think he's very talented and passionate about the book, and I think this particular novel is so interesting visually that I think something could be done as a film, but they don't have all the money yet and it's been dragging on for years and I don't know if it will ever happen.

I helped him write the script; we actually did it together. He did a first version then I re-wrote it and then we did a third version together, so I'm implicated and we'll see what happens but I haven't had any news for a long time. I have a feeling things aren't going so well. But that's the movie business. It's absolutely unstable and ridiculous.

He wants to shoot it in Buenos Aires and he's found locations that are very interesting and would work. It's not going to be a film with a high budget, so he's going to have to be very clever in how he figures it out if he gets to make it.

What do you think people would say about collaborating with Paul Auster?

So far I haven't had any complaints.